Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Heavy-hitting investors are snapping up US government bonds with longer maturities, betting the pain in the Treasury market is nearly over and an elusive slowdown in the US economy may be on the horizon.

Money managers including Pimco, Janus Henderson, Vanguard and BlackRock are taking the plunge — a bold bet after a multi-month rout in bond prices that has repeatedly wrongfooted asset managers and sent the 10-year Treasury yield above 5 per cent this week for the first time since 2007.

The US economy is in strikingly rude health for now. Data this week showed an annualised growth rate of 4.9 per cent in the third quarter. But investors are starting to plot out what happens a little further down the line, especially as the jump in bond yields jacks up borrowing costs for companies, households and the government. If the long-awaited slowdown does bite, that should push bond prices back up.

“These higher yields will eventually slow growth,” said Mike Cudzil, a portfolio manager at bond giant Pimco. “We are set up to play offence in the event the economy begins to slow.”

Bonds that mature far out in to the future, 10 years or more, have suffered particularly badly as markets have struggled to digest the message from the US Federal Reserve that interest rates will stay at high levels for the long haul, and as the economy has confounded downbeat forecasts. But Cudzil said that sector of the market was due a reprieve.

“We’re adding duration to our portfolios,” said Cudzil, referring to longer-dated debt. “We’re going overweight duration. And we’re overweight fixed income relative to equities.”

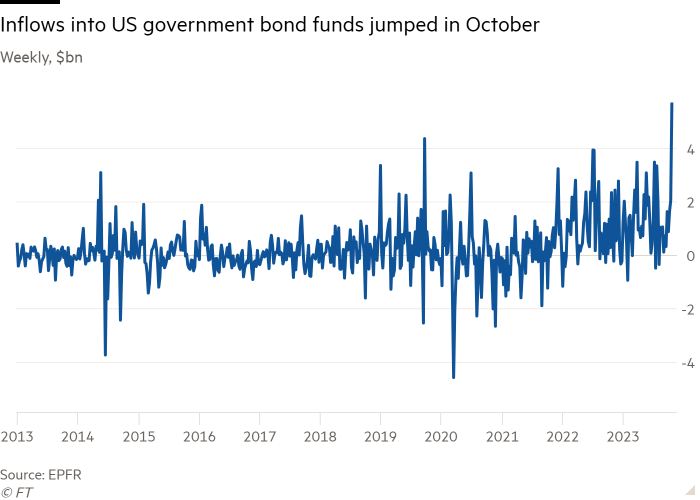

Confidence in a rebound in bonds is fanning across the market. EPFR data shows weekly inflows in to long-dated US sovereign debt funds were the highest on record in the seven days ending on October 25, at $5.7bn.

Dipping in to bonds, especially long-dated bonds, has burnt investors repeatedly this year. Analysts and economists have been expecting a recession all year long, but a slowdown has yet to materialise. Yields have risen relentlessly, punishing investors who piled into fixed income betting that 2023 would be the “year of the bond”. The 10-year Treasury, which had its worst year on record in 2022, is down again this year.

In a note this month, BlackRock said it had adjusted its positioning in long-dated bonds, although it remains cautious on the debt longer-term.

“We have been underweight long-term US Treasuries since late 2020 as we saw the new macro regime heralding higher rates,” it said. “US 10-year yields at 16-year highs show they have adjusted a lot, but we don’t think the process is over. We now turn tactically neutral as policy rates near their peak.”

The analysts noted, however, that BlackRock expects to remain strategically underweight longer-term.

Investors are confident the Fed will keep interest rates at the current high level for a long period, but expectations it will raise rates again have diminished. Traders in the futures market put the chances that the Fed would raise interest rates at their meeting next week at less than 2 per cent. The odds of a rise by December are around 20 per cent.

Jim Cielinski, global head of fixed income at Janus Henderson Investors, nonetheless said it can make sense for certain portfolios to scoop up long-dated bonds, given the sell-off has left the regular interest payments they offer at the highest level in years. “We are going long duration in the more aggressive strategies,” he said. “If you can bear the volatility, the attractive yields plus opportunity for capital appreciation is there over the next six to 12 months. But people are so burned and so scarred because they have been calling a recession for the last year.”

Longer-dated Treasury bonds are a traditional haven asset, a magnet to investors during moments of market volatility and geopolitical instability. Some investors said they are buying in order to protect their portfolios from a potential slide in riskier assets like equities.

“I think the key thing with bonds right now is that when economic news really turns, like back in March during the Silicon Valley Bank turmoil or when there is a recession, only bonds actually protect your capital,” said Ales Koutny, head of international fixed income at Vanguard.

Koutny said the short-term outlook for the 10-year is uncertain, but “taking a step back” the next large move in yields is likely to be lower. “We think that from a pure-risk reward perspective, allocating into bonds, even at the 10-year point, makes a lot of sense here.”